Jonah Cader

How Deep is the Feature Analysis underlying Rapid Visual Categorization?

Jun 03, 2016

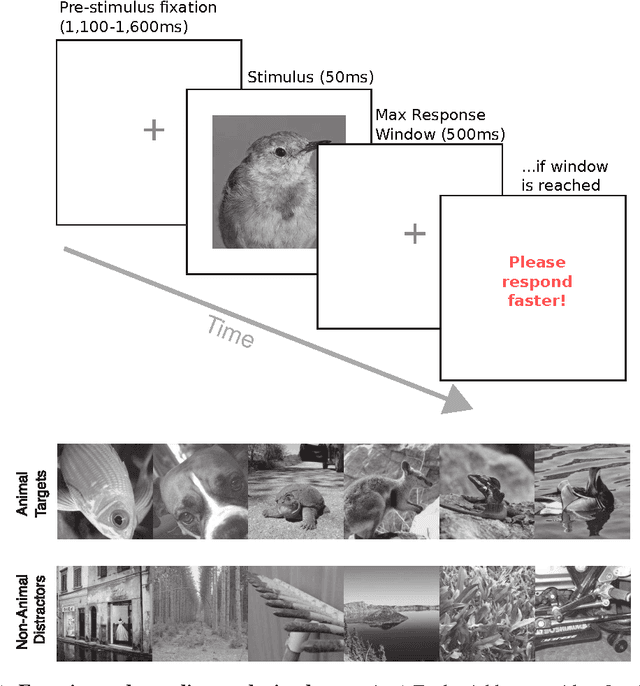

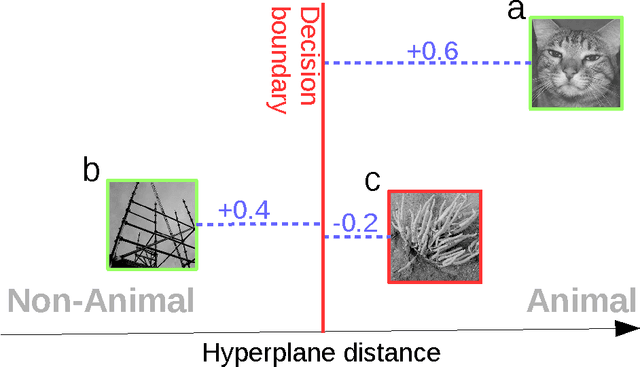

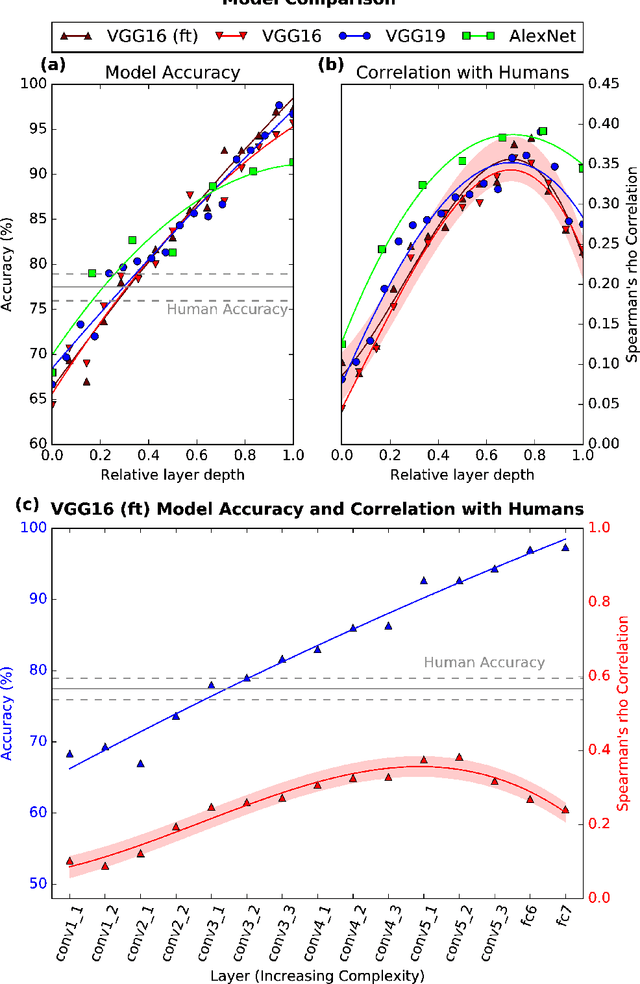

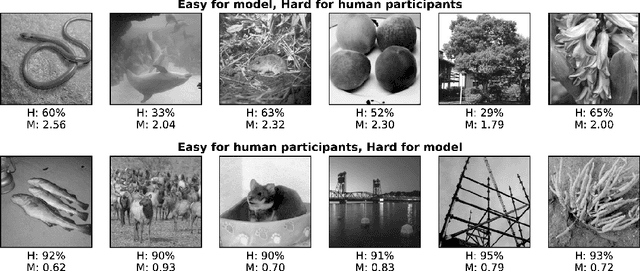

Abstract:Rapid categorization paradigms have a long history in experimental psychology: Characterized by short presentation times and speedy behavioral responses, these tasks highlight the efficiency with which our visual system processes natural object categories. Previous studies have shown that feed-forward hierarchical models of the visual cortex provide a good fit to human visual decisions. At the same time, recent work in computer vision has demonstrated significant gains in object recognition accuracy with increasingly deep hierarchical architectures. But it is unclear how well these models account for human visual decisions and what they may reveal about the underlying brain processes. We have conducted a large-scale psychophysics study to assess the correlation between computational models and human participants on a rapid animal vs. non-animal categorization task. We considered visual representations of varying complexity by analyzing the output of different stages of processing in three state-of-the-art deep networks. We found that recognition accuracy increases with higher stages of visual processing (higher level stages indeed outperforming human participants on the same task) but that human decisions agree best with predictions from intermediate stages. Overall, these results suggest that human participants may rely on visual features of intermediate complexity and that the complexity of visual representations afforded by modern deep network models may exceed those used by human participants during rapid categorization.

Add to Chrome

Add to Chrome Add to Firefox

Add to Firefox Add to Edge

Add to Edge