Jaber R. Mianroodi

Divergence-free neural operators for stress field modeling in polycrystalline materials

Aug 27, 2024Abstract:The purpose of the current work is the development and comparison of Fourier neural operators (FNOs) for surrogate modeling of the quasi-static mechanical response of polycrystalline materials. Three types of such FNOs are considered here: a physics-guided FNO (PgFNO), a physics-informed FNO (PiFNO), and a physics-encoded FNO (PeFNO). These are trained and compared with the help of stress field data from a reference model for heterogeneous elastic materials with a periodic grain microstructure. Whereas PgFNO training is based solely on these data, that of the PiFNO and PeFNO is in addition constrained by the requirement that stress fields satisfy mechanical equilibrium, i.e., be divergence-free. The difference between the PiFNO and PeFNO lies in how this constraint is taken into account; in the PiFNO, it is included in the loss function, whereas in the PeFNO, it is "encoded" in the operator architecture. In the current work, this encoding is based on a stress potential and Fourier transforms. As a result, only the training of the PiFNO is constrained by mechanical equilibrium; in contrast, mechanical equilibrium constrains both the training and output of the PeFNO. Due in particular to this, stress fields calculated by the trained PeFNO are significantly more accurate than those calculated by the trained PiFNO in the example cases considered.

Computational Discovery of Energy-Efficient Heat Treatment for Microstructure Design using Deep Reinforcement Learning

Sep 22, 2022

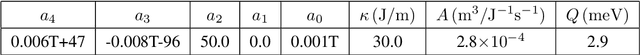

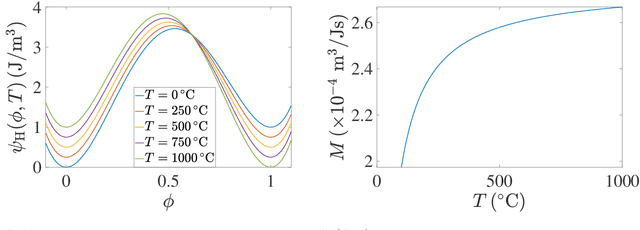

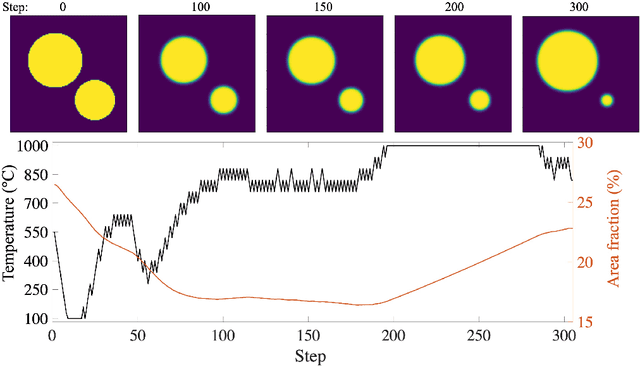

Abstract:Deep Reinforcement Learning (DRL) is employed to develop autonomously optimized and custom-designed heat-treatment processes that are both, microstructure-sensitive and energy efficient. Different from conventional supervised machine learning, DRL does not rely on static neural network training from data alone, but a learning agent autonomously develops optimal solutions, based on reward and penalty elements, with reduced or no supervision. In our approach, a temperature-dependent Allen-Cahn model for phase transformation is used as the environment for the DRL agent, serving as the model world in which it gains experience and takes autonomous decisions. The agent of the DRL algorithm is controlling the temperature of the system, as a model furnace for heat-treatment of alloys. Microstructure goals are defined for the agent based on the desired microstructure of the phases. After training, the agent can generate temperature-time profiles for a variety of initial microstructure states to reach the final desired microstructure state. The agent's performance and the physical meaning of the heat-treatment profiles generated are investigated in detail. In particular, the agent is capable of controlling the temperature to reach the desired microstructure starting from a variety of initial conditions. This capability of the agent in handling a variety of conditions paves the way for using such an approach also for recycling-oriented heat treatment process design where the initial composition can vary from batch to batch, due to impurity intrusion, and also for the design of energy-efficient heat treatments. For testing this hypothesis, an agent without penalty on the total consumed energy is compared with one that considers energy costs. The energy cost penalty is imposed as an additional criterion on the agent for finding the optimal temperature-time profile.

Accelerating phase-field-based simulation via machine learning

May 04, 2022

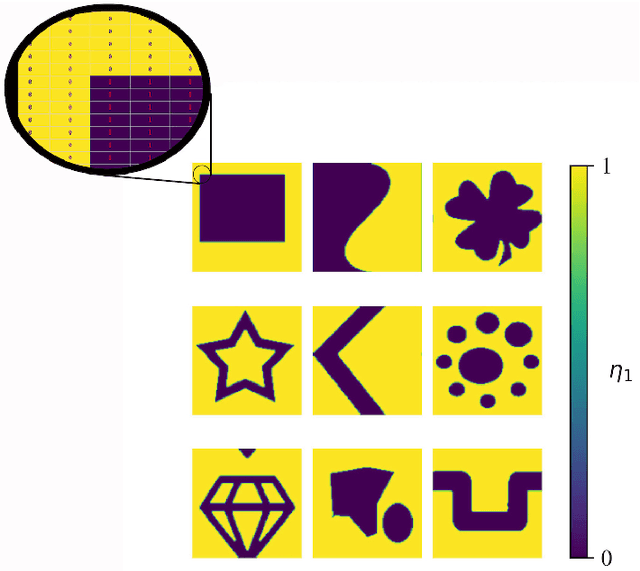

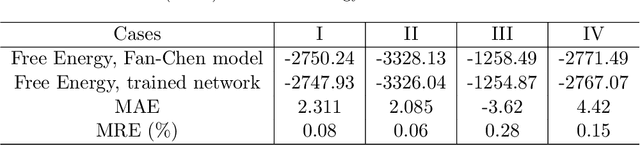

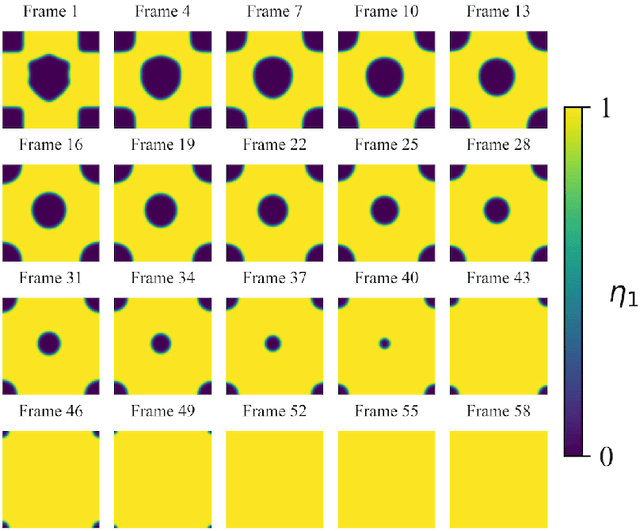

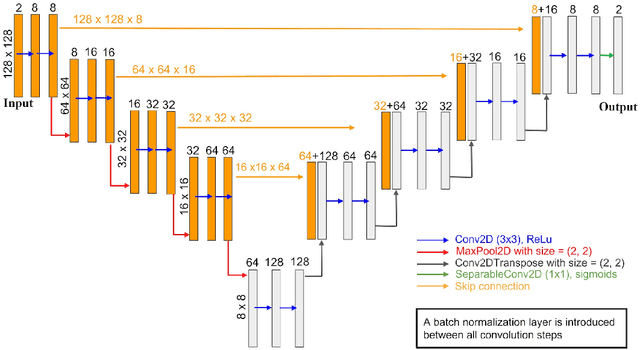

Abstract:Phase-field-based models have become common in material science, mechanics, physics, biology, chemistry, and engineering for the simulation of microstructure evolution. Yet, they suffer from the drawback of being computationally very costly when applied to large, complex systems. To reduce such computational costs, a Unet-based artificial neural network is developed as a surrogate model in the current work. Training input for this network is obtained from the results of the numerical solution of initial-boundary-value problems (IBVPs) based on the Fan-Chen model for grain microstructure evolution. In particular, about 250 different simulations with varying initial order parameters are carried out and 200 frames of the time evolution of the phase fields are stored for each simulation. The network is trained with 90% of this data, taking the $i$-th frame of a simulation, i.e. order parameter field, as input, and producing the $(i+1)$-th frame as the output. Evaluation of the network is carried out with a test dataset consisting of 2200 microstructures based on different configurations than originally used for training. The trained network is applied recursively on initial order parameters to calculate the time evolution of the phase fields. The results are compared to the ones obtained from the conventional numerical solution in terms of the errors in order parameters and the system's free energy. The resulting order parameter error averaged over all points and all simulation cases is 0.005 and the relative error in the total free energy in all simulation boxes does not exceed 1%.

Add to Chrome

Add to Chrome Add to Firefox

Add to Firefox Add to Edge

Add to Edge