Andrea W Wen-Yi

Cheaper, Better, Faster, Stronger: Robust Text-to-SQL without Chain-of-Thought or Fine-Tuning

May 20, 2025Abstract:LLMs are effective at code generation tasks like text-to-SQL, but is it worth the cost? Many state-of-the-art approaches use non-task-specific LLM techniques including Chain-of-Thought (CoT), self-consistency, and fine-tuning. These methods can be costly at inference time, sometimes requiring over a hundred LLM calls with reasoning, incurring average costs of up to \$0.46 per query, while fine-tuning models can cost thousands of dollars. We introduce "N-rep" consistency, a more cost-efficient text-to-SQL approach that achieves similar BIRD benchmark scores as other more expensive methods, at only \$0.039 per query. N-rep leverages multiple representations of the same schema input to mitigate weaknesses in any single representation, making the solution more robust and allowing the use of smaller and cheaper models without any reasoning or fine-tuning. To our knowledge, N-rep is the best-performing text-to-SQL approach in its cost range.

Do Chinese models speak Chinese languages?

Mar 31, 2025

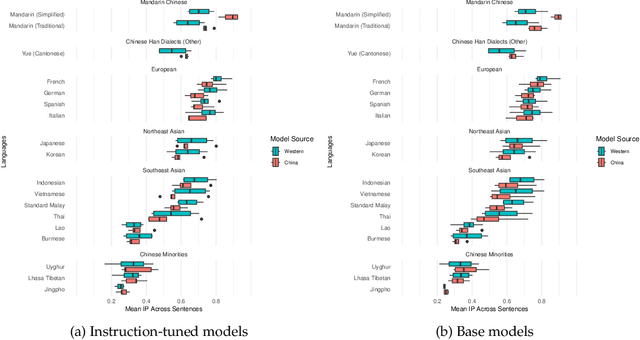

Abstract:The release of top-performing open-weight LLMs has cemented China's role as a leading force in AI development. Do these models support languages spoken in China? Or do they speak the same languages as Western models? Comparing multilingual capabilities is important for two reasons. First, language ability provides insights into pre-training data curation, and thus into resource allocation and development priorities. Second, China has a long history of explicit language policy, varying between inclusivity of minority languages and a Mandarin-first policy. To test whether Chinese LLMs today reflect an agenda about China's languages, we test performance of Chinese and Western open-source LLMs on Asian regional and Chinese minority languages. Our experiments on Information Parity and reading comprehension show Chinese models' performance across these languages correlates strongly (r=0.93) with Western models', with the sole exception being better Mandarin. Sometimes, Chinese models cannot identify languages spoken by Chinese minorities such as Kazakh and Uyghur, even though they are good at French and German. These results provide a window into current development priorities, suggest options for future development, and indicate guidance for end users.

Automate or Assist? The Role of Computational Models in Identifying Gendered Discourse in US Capital Trial Transcripts

Jul 17, 2024Abstract:The language used by US courtroom actors in criminal trials has long been studied for biases. However, systematic studies for bias in high-stakes court trials have been difficult, due to the nuanced nature of bias and the legal expertise required. New large language models offer the possibility to automate annotation, saving time and cost. But validating these approaches requires both high quantitative performance as well as an understanding of how automated methods fit in existing workflows, and what they really offer. In this paper we present a case study of adding an automated system to a complex and high-stakes problem: identifying gender-biased language in US capital trials for women defendants. Our team of experienced death-penalty lawyers and NLP technologists pursued a three-phase study: first annotating manually, then training and evaluating computational models, and finally comparing human annotations to model predictions. Unlike many typical NLP tasks, annotating for gender bias in months-long capital trials was a complicated task that involves with many individual judgment calls. In contrast to standard arguments for automation that are based on efficiency and scalability, legal experts found the computational models most useful in challenging their personal bias in annotation and providing opportunities to refine and build consensus on rules for annotation. This suggests that seeking to replace experts with computational models is both unrealistic and undesirable. Rather, computational models offer valuable opportunities to assist the legal experts in annotation-based studies.

How Chinese are Chinese Language Models? The Puzzling Lack of Language Policy in China's LLMs

Jul 12, 2024Abstract:Contemporary language models are increasingly multilingual, but Chinese LLM developers must navigate complex political and business considerations of language diversity. Language policy in China aims at influencing the public discourse and governing a multi-ethnic society, and has gradually transitioned from a pluralist to a more assimilationist approach since 1949. We explore the impact of these influences on current language technology. We evaluate six open-source multilingual LLMs pre-trained by Chinese companies on 18 languages, spanning a wide range of Chinese, Asian, and Anglo-European languages. Our experiments show Chinese LLMs performance on diverse languages is indistinguishable from international LLMs. Similarly, the models' technical reports also show lack of consideration for pretraining data language coverage except for English and Mandarin Chinese. Examining Chinese AI policy, model experiments, and technical reports, we find no sign of any consistent policy, either for or against, language diversity in China's LLM development. This leaves a puzzling fact that while China regulates both the languages people use daily as well as language model development, they do not seem to have any policy on the languages in language models.

Hyperpolyglot LLMs: Cross-Lingual Interpretability in Token Embeddings

Nov 29, 2023Abstract:Cross-lingual transfer learning is an important property of multilingual large language models (LLMs). But how do LLMs represent relationships between languages? Every language model has an input layer that maps tokens to vectors. This ubiquitous layer of language models is often overlooked. We find that similarities between these input embeddings are highly interpretable and that the geometry of these embeddings differs between model families. In one case (XLM-RoBERTa), embeddings encode language: tokens in different writing systems can be linearly separated with an average of 99.2% accuracy. Another family (mT5) represents cross-lingual semantic similarity: the 50 nearest neighbors for any token represent an average of 7.61 writing systems, and are frequently translations. This result is surprising given that there is no explicit parallel cross-lingual training corpora and no explicit incentive for translations in pre-training objectives. Our research opens the door for investigations in 1) The effect of pre-training and model architectures on representations of languages and 2) The applications of cross-lingual representations embedded in language models.

Add to Chrome

Add to Chrome Add to Firefox

Add to Firefox Add to Edge

Add to Edge