Risk aversion as an evolutionary adaptation

Paper and Code

Oct 23, 2013

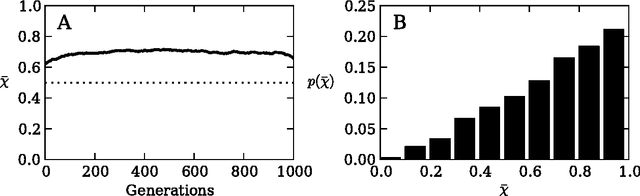

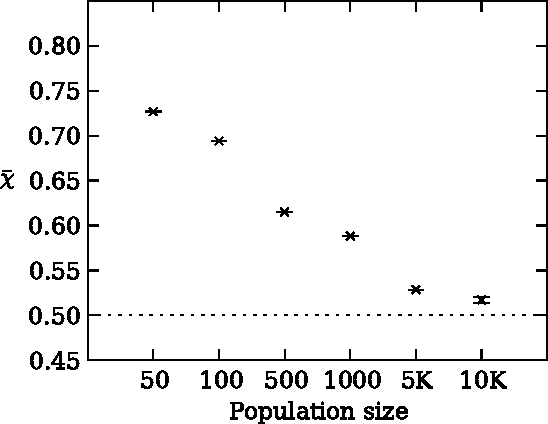

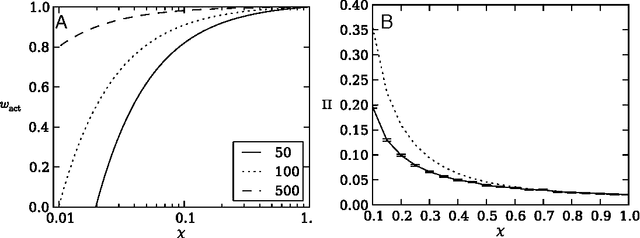

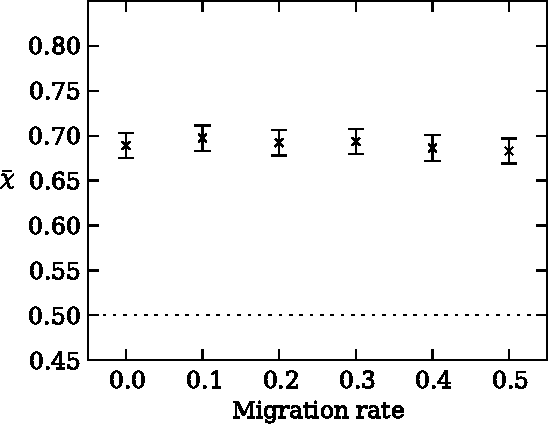

Risk aversion is a common behavior universal to humans and animals alike. Economists have traditionally defined risk preferences by the curvature of the utility function. Psychologists and behavioral economists also make use of concepts such as loss aversion and probability weighting to model risk aversion. Neurophysiological evidence suggests that loss aversion has its origins in relatively ancient neural circuitries (e.g., ventral striatum). Could there thus be an evolutionary origin to risk avoidance? We study this question by evolving strategies that adapt to play the equivalent mean payoff gamble. We hypothesize that risk aversion in the equivalent mean payoff gamble is beneficial as an adaptation to living in small groups, and find that a preference for risk averse strategies only evolves in small populations of less than 1,000 individuals, while agents exhibit no such strategy preference in larger populations. Further, we discover that risk aversion can also evolve in larger populations, but only when the population is segmented into small groups of around 150 individuals. Finally, we observe that risk aversion only evolves when the gamble is a rare event that has a large impact on the individual's fitness. These findings align with earlier reports that humans lived in small groups for a large portion of their evolutionary history. As such, we suggest that rare, high-risk, high-payoff events such as mating and mate competition could have driven the evolution of risk averse behavior in humans living in small groups.

Add to Chrome

Add to Chrome Add to Firefox

Add to Firefox Add to Edge

Add to Edge