Learning the Ranking of Causal Effects with Confounded Data

Paper and Code

Jun 25, 2022

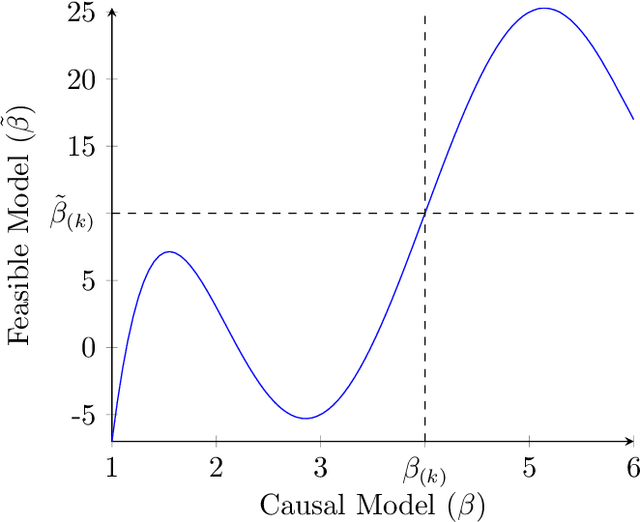

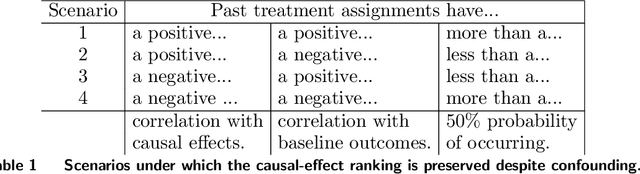

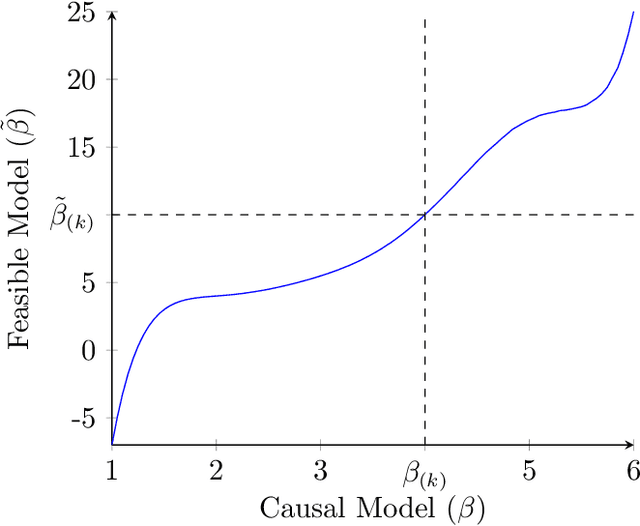

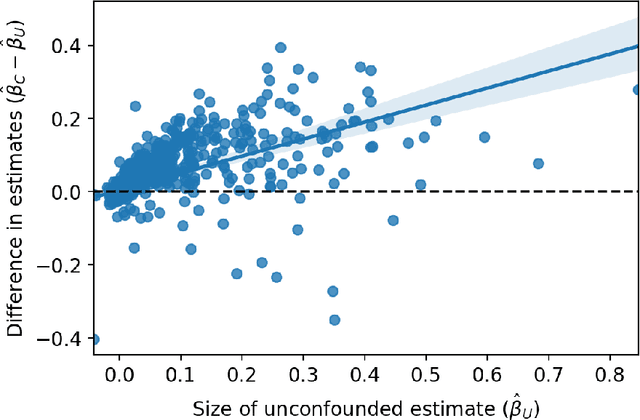

Decision makers often want to identify the individuals for whom some intervention or treatment will be most effective in order to decide who to treat. In such cases, decision makers would ideally like to rank potential recipients of the treatment according to their individual causal effects. However, the historical data available to estimate the causal effects could be confounded, and as a result, accurately estimating the effects could be impossible. We propose a new and less restrictive assumption about historical data, called the ranking preservation assumption (RPA), under which the ranking of the individual effects can be consistently estimated even if the effects themselves cannot be accurately estimated. Importantly, we find that confounding can be helpful for the estimation of the causal-effect ranking when the confounding bias is larger for individuals with larger causal effects, and that even when this is not the case, any detrimental impact of confounding can be corrected with larger training data when the RPA is met. We then analytically show that the RPA can be met in a variety of scenarios, including common business applications such as online advertising and customer retention. We support this finding with an empirical example in the context of online advertising. The example also shows how to evaluate the decision making of a confounded model in practice. The main takeaway is that what might traditionally be considered "good" data for causal estimation (i.e., unconfounded data) may not be necessary to make good causal decisions, so treatment assignment methods may work better than we give them credit for in the presence of confounding.

Add to Chrome

Add to Chrome Add to Firefox

Add to Firefox Add to Edge

Add to Edge